Language:

-

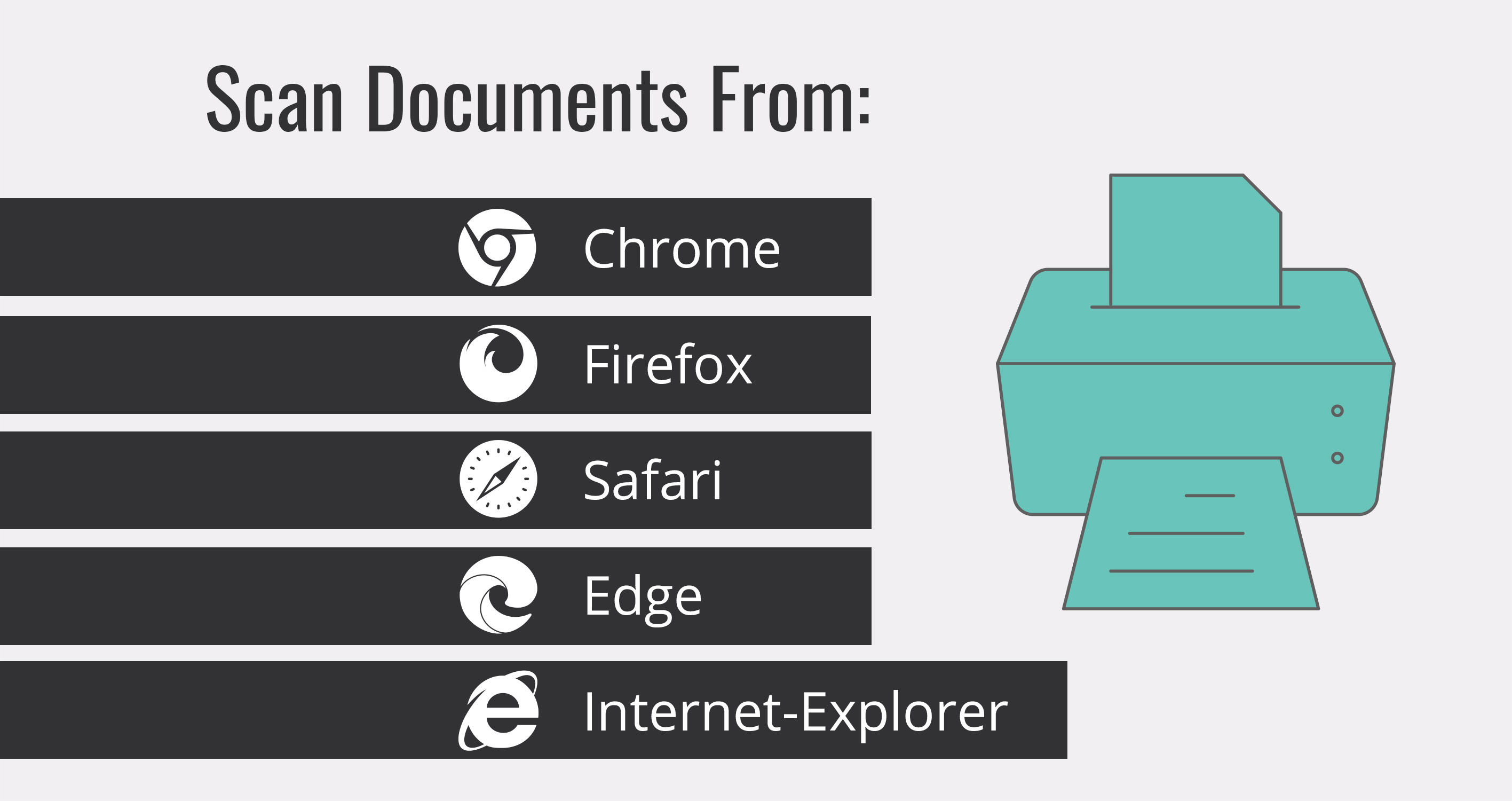

مجموعة أدوات تطوير البرمجيات لمسح الوثائق لنشر تطبيقات الويب الخاصة بك بسرعة موثوق بها من قبل أكثر من 5300 شركة لقوتها وأمانها Dynamic Web TWAIN هي مجموعة أدوات تطوير البرمجيات لمسح الوثائق على المتصفح مصممة للسرعة، الدقة والقدرة على التوسع. ببضعة أسطر من JavaScript، يمكنك تطوير تطبيقات قوية لمسح الوثائق...

Read more › -

وظيفة مسح المستندات هي مكون حيوي لمطور البرمجيات الذي يقوم ببناء موقع ويب أو نظام إدارة المحتوى أو نظام التشغيل المكتبي. هناك العديد من برامج تشغيل المسح المختلفة المتاحة في السوق: ماسح TWAIN ماسح WIA ماسح ISIS ماسح SANE من الطبيعي أن تشعر بالارتباك حول ما هو الحل الأفضل بالنسبة...

Read more › -

أنظمة إدارة المستندات القائمة على الويب والتي تستخدم JavaScript / JQuery للجانب العميل و PHP للجانب الخادم تستخدم على نطاق واسع من قبل الشركات. تمكن هذه الأنظمة المستخدمين من مسح المستندات من المتصفح باستخدام الماسح الضوئي للجانب العميل وتحريرها وتحميل الصور على قاعدة بيانات على الخادم. ومع ذلك، قد يستخدم...

Read more ›